final-wineproject

Final Project: Wine Quality

Annette Broeren

Tanlin Hung

Rick Spitzer

Kate Spitzer

To run our wine quality site, visit: https://ucsd-winequality.herokuapp.com/

To take a look at the code, go here: https://github.com/kmspitzer/final-wineproject

Purpose

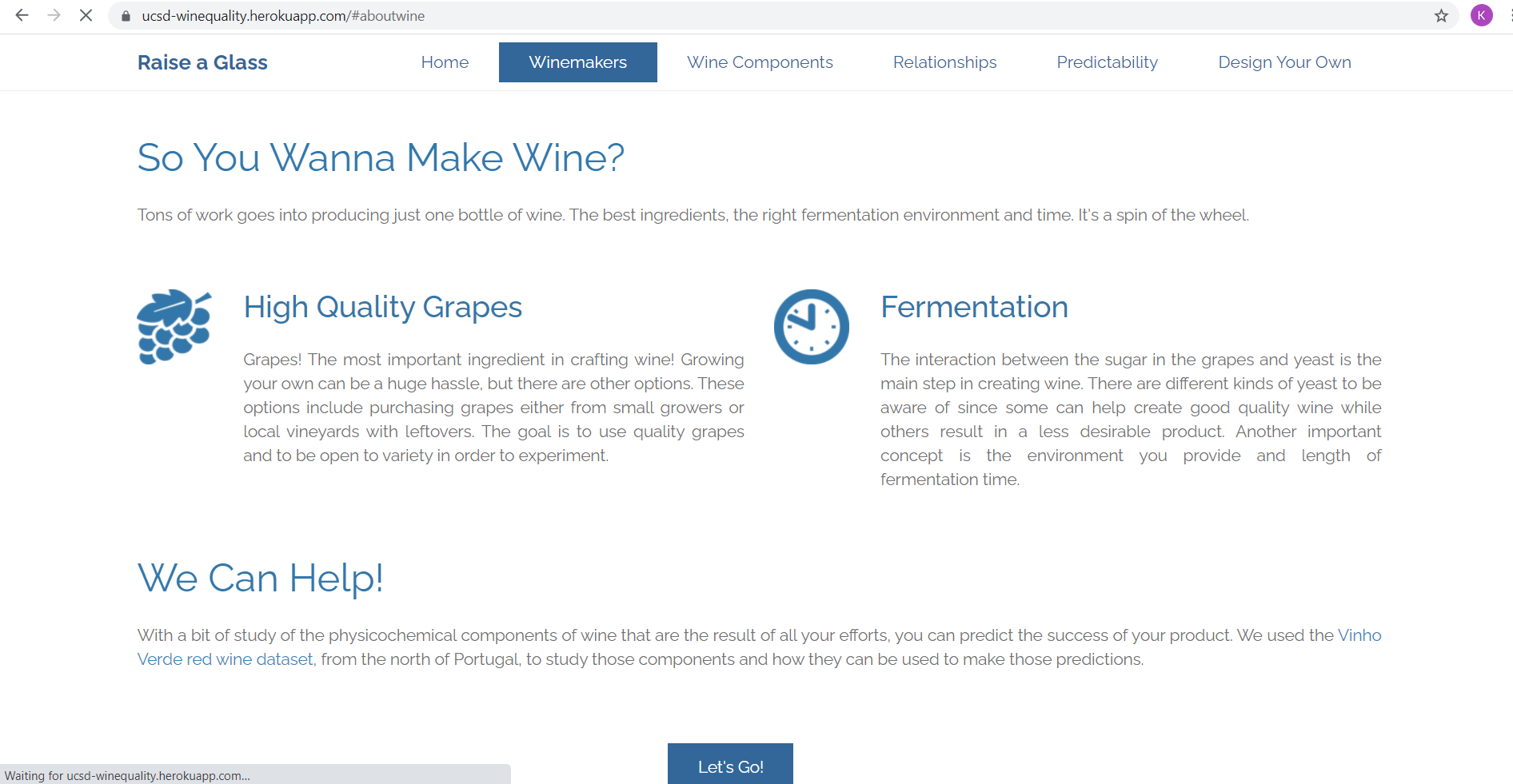

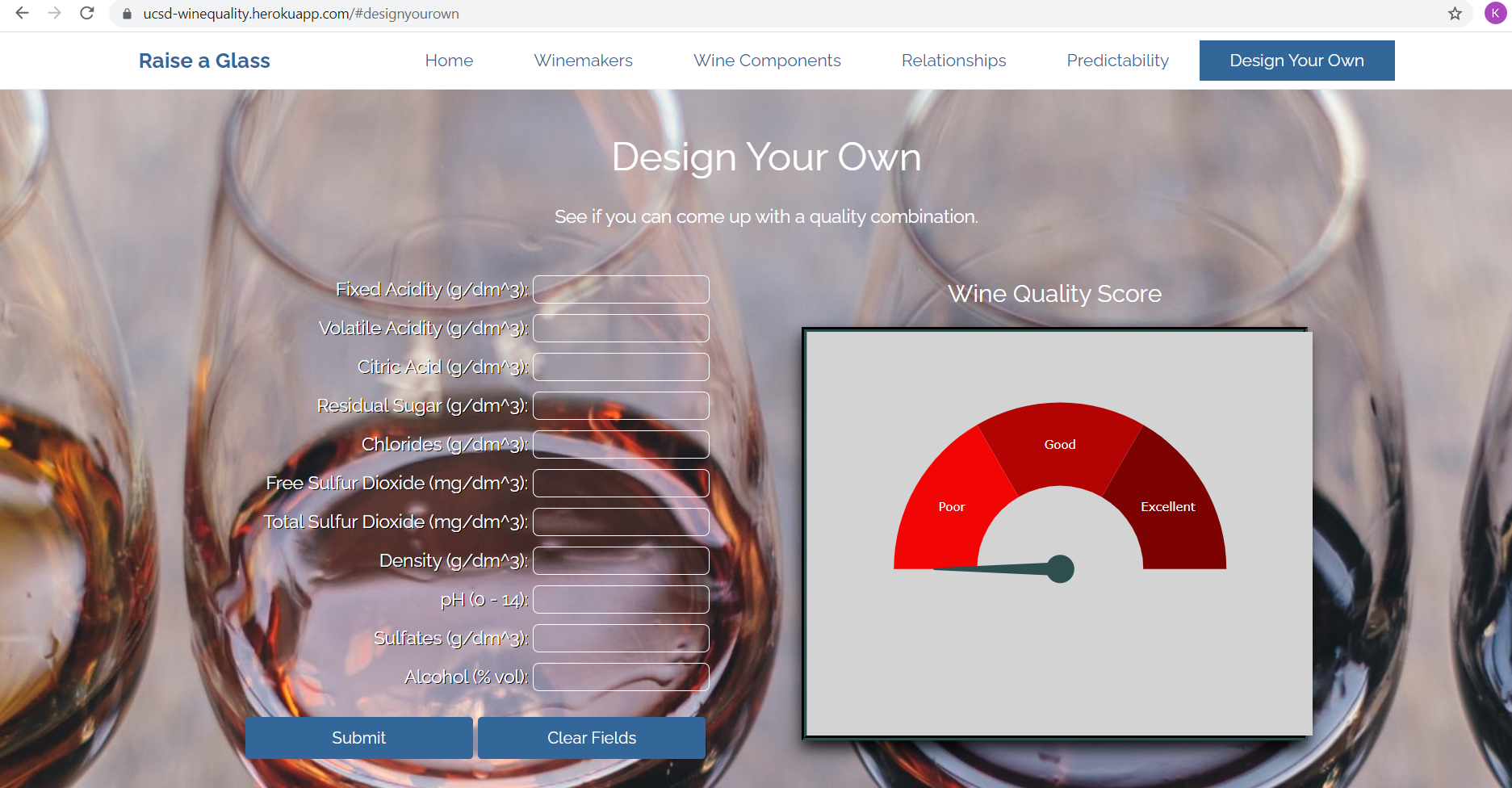

The purpose of this project was to create an interactive app for prospective winemakers to test expected wine quality based on physicochemical components.

Data Set

A Vinho Verde wine quality data set was chosen made available by UCI Machine Learning: https://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml/datasets/wine+quality. Source:

Paulo Cortez, University of Minho, Guimarães, Portugal, http://www3.dsi.uminho.pt/pcortez A. Cerdeira, F. Almeida, T. Matos and J. Reis, Viticulture Commission of the Vinho Verde Region(CVRVV), Porto, Portugal @2009

Data Set Information

The two datasets are related to red and white variants of the Portuguese “Vinho Verde” wine. For more details, consult: [Web Link] or the reference [Cortez et al., 2009]. Due to privacy and logistic issues, only physicochemical (inputs) and sensory (the output) variables are available (e.g. there is no data about grape types, wine brand, wine selling price, etc.).

These datasets can be viewed as classification or regression tasks. The classes are ordered and not balanced (e.g. there are many more normal wines than excellent or poor ones). Outlier detection algorithms could be used to detect the few excellent or poor wines. Also, we are not sure if all input variables are relevant. So it could be interesting to test feature selection methods.

We chose to concentrate on the red wine data.

Citation Requested:

{}. Cortez, A. Cerdeira, F. Almeida, T. Matos and J. Reis. Modeling wine preferences by data mining from physicochemical properties. In Decision Support Systems, Elsevier, 47(4):547-553, 2009.

The data set contains 2 CSV files, one for white wines and one for red wine. During our exploration we found that between the red wine and white wine, the results were not noticably different. Therefore, we decided to simplify our model and only work with the red wine data set (approximately 1,600 records).

General Information

Courtesy Wikipedia, edited for length: Vinho Verde refers to Portuguese wine that originated in the historic Minho province in the far north of the country. Vinho Verde is not a grape variety, it is a DOC for the production of wine. The name means “green wine,” but translates as “young wine”, with wine being released three to six months after the grapes are harvested. The region is characterized by its many small growers, which numbered around 19,000 as of 2014. Many of these growers used to train their vines high off the ground, up trees, fences, and even telephone poles so that they could cultivate vegetable crops below the vines that their families may use as a food source. Red wine is produced from whole dark red or black graphes including the skin. White wine is made from white grapes with no skins or seeds. Sounds delicious? Read on …

Understanding Wine Attributes and Properties

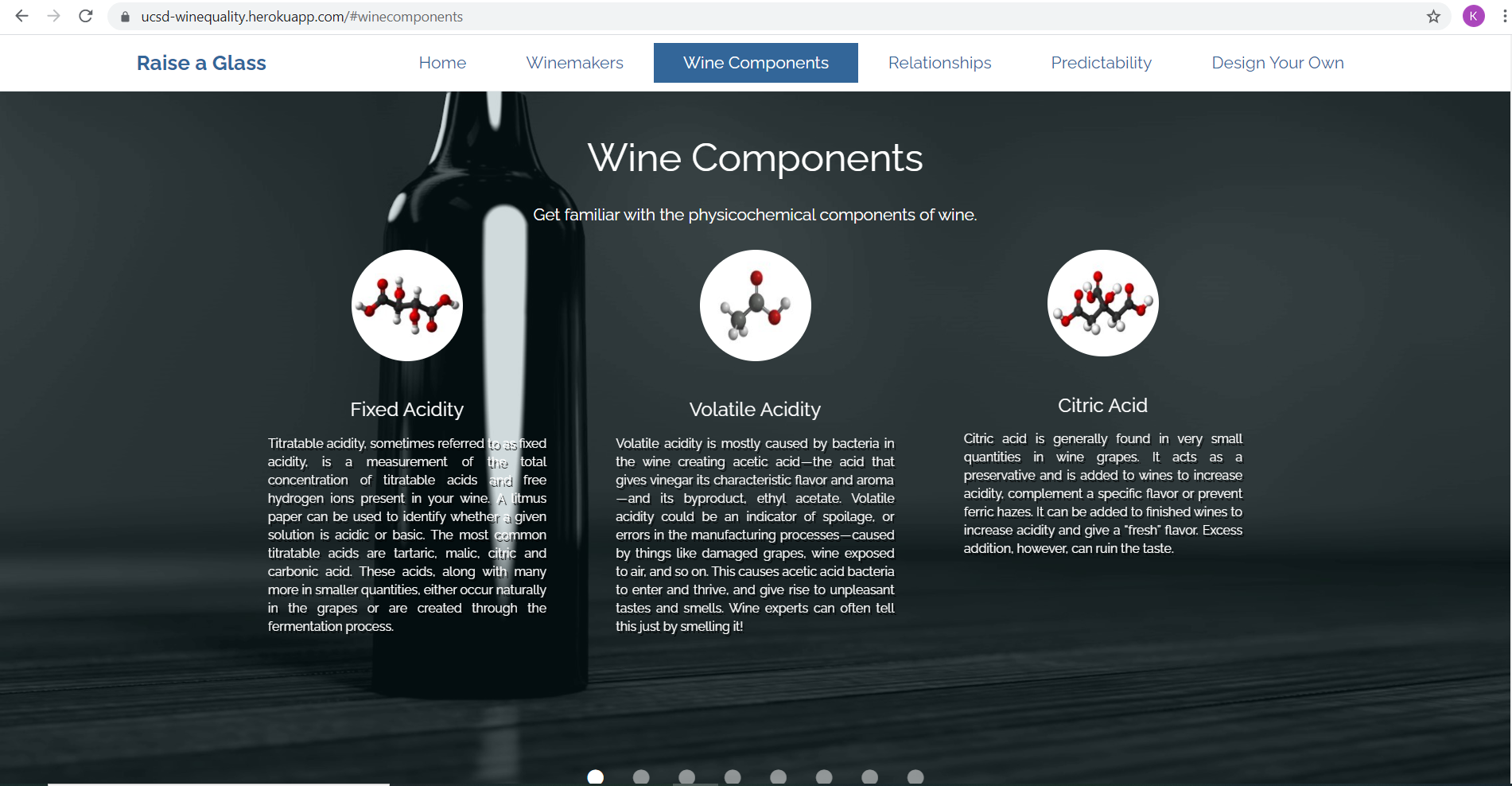

Fixed Acidity

Titratable acidity, sometimes referred to as fixed acidity, is a measurement of the total concentration of titratable acids and free hydrogen ions present in your wine. A litmus paper can be used to identify whether a given solution is acidic or basic. The most common titratable acids are tartaric, malic, citric and carbonic acid. These acids, along with many more in smaller quantities, either occur naturally in the grapes or are created through the fermentation process.

Volatile Acidity

Volatile acidity is mostly caused by bacteria in the wine creating acetic acid — the acid that gives vinegar its characteristic flavor and aroma — and its byproduct, ethyl acetate. Volatile acidity could be an indicator of spoilage, or errors in the manufacturing processes — caused by things like damaged grapes, wine exposed to air, and so on. This causes acetic acid bacteria to enter and thrive, and give rise to unpleasant tastes and smells. Wine experts can often tell this just by smelling it!

Citric Acid

Citric acid is generally found in very small quantities in wine grapes. It acts as a preservative and is added to wines to increase acidity, complement a specific flavor or prevent ferric hazes. It can be added to finished wines to increase acidity and give a “fresh” flavor. Excess addition, however, can ruin the taste.

Residual Sugars

Residual Sugar, or RS for short, refers to any natural grape sugars that are leftover after fermentation ceases (whether on purpose or not). The juice of wine grapes starts out intensely sweet, and fermentation uses up that sugar as the yeasts feast upon it. During winemaking, yeast typically converts all the sugar into alcohol making a dry wine. However, sometimes not all the sugar is fermented by the yeast, leaving some sweetness leftover. To make a wine that tastes good, the key is to have a perfect balance between the sweetness and the sourness in the drink.

Chloride

The amount of chlorides present in a wine is usually an indicator of its “saltiness.” This is usually influenced by the territory where the wine grapes grew, cultivation methods, and also the grape type. Too much saltiness is considered undesirable. The right proportion can make the wine more savory.

Sulphur Dioxide levels

Sulfur dioxide exists in wine in free and bound forms, and the combinations are referred to as total SO2. It’s the most common preservative used, usually added by wine makers to protect the wine from negative effects of exposure to air and oxygen. Wines with added sulphur dioxide contents usually have “Contains Sulphites” on their labels. It acts as a sanitizing agent — adding it usually kills unwanted bacteria or yeast that might enter the wine and spoil its taste and aroma. It was first used in winemaking by the Romans, when they discovered that burning sulfur candles inside empty wine vessels keeps them fresh and free from vinegar smell.

Density

Also known as specific gravity, it can be used to measure the alcohol concentration in wines. During fermentation, the sugar in the juice is converted into ethanol with carbon dioxide as a waste gas. Monitoring the density during the process allows for optimal control of this conversion step for highest quality wines. Sweeter wines generally have higher densities.

pH

pH stands for power of hydrogen, which is a measurement of the hydrogen ion concentration in the solution. Generally, solutions with a pH value less than 7 are considered acidic, with some of the strongest acids being close to 0. Solutions above 7 are considered alkaline or basic. The pH value of water is 7, as it is neither an acid nor a base.

Sulphates

Sulfates are salts of sulfuric acid. They aren’t involved in wine production, but some beer makers use calcium sulfate — also known as brewers’ gypsum — to correct mineral deficiencies in water during the brewing process. It also adds a bit of a “sharp” taste.

Alcohol

Alcohol is formed as a result of yeast converting sugar during the fermentation process.

Data Cleaning and Exploration

Our dataset contained a relatively small number of null values. We ran tests to determine the best way to handle this situation; to remove rows with null datapoints, or to populate null values with the mean for the column. Both approaches were tested to see if there was an affect on the outcome, and we found any difference to be negligible. We decided to populate with the column mean.

Looking at the distribution of datapoints by feature, we saw a few outliers. We chose not to remove them from our dataset, as their inclusion had no measurable affect on our outcome.

As with most who explored this dataset, we too found that most wines from the data set are of good quality: only few are poor or excellent. Sounds like Vinho Verde is a pretty solid place to grow grapes and make wine, right?! In order to balance our data, we used the imbalanced learning method SMOTE(). This significantly improved our results.

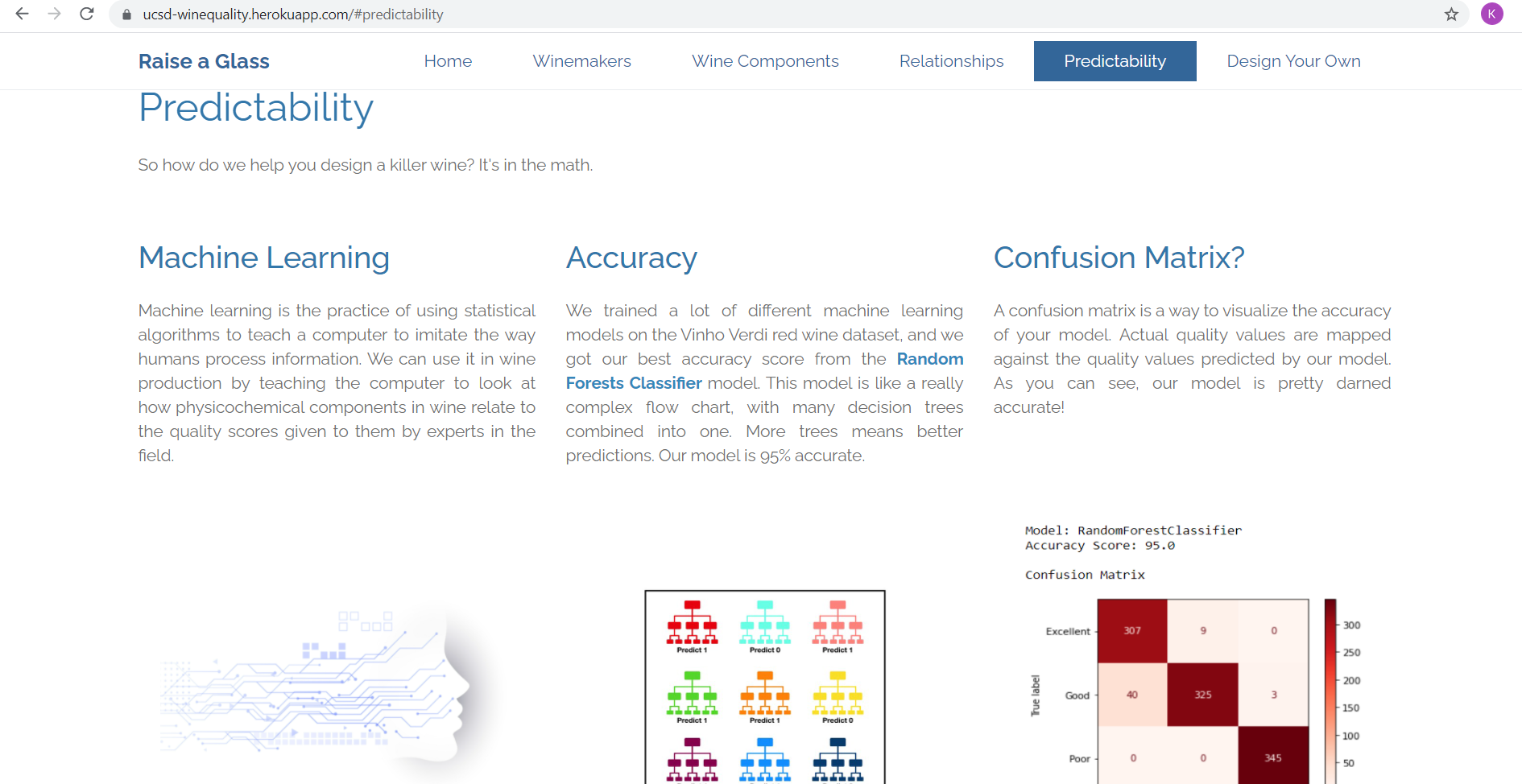

Machine Learning Model

Once we normalized the data, we explored several classifiers:

K Nearest Neighbors

Decision Tree

Random Forest

Random Forest Regressor

Stochastic Gradient Descent

Support Vector Classification

Linear Support Vector Classification

AdaBoost Classifier

Gradient Boost Classifier

XGB Classifier

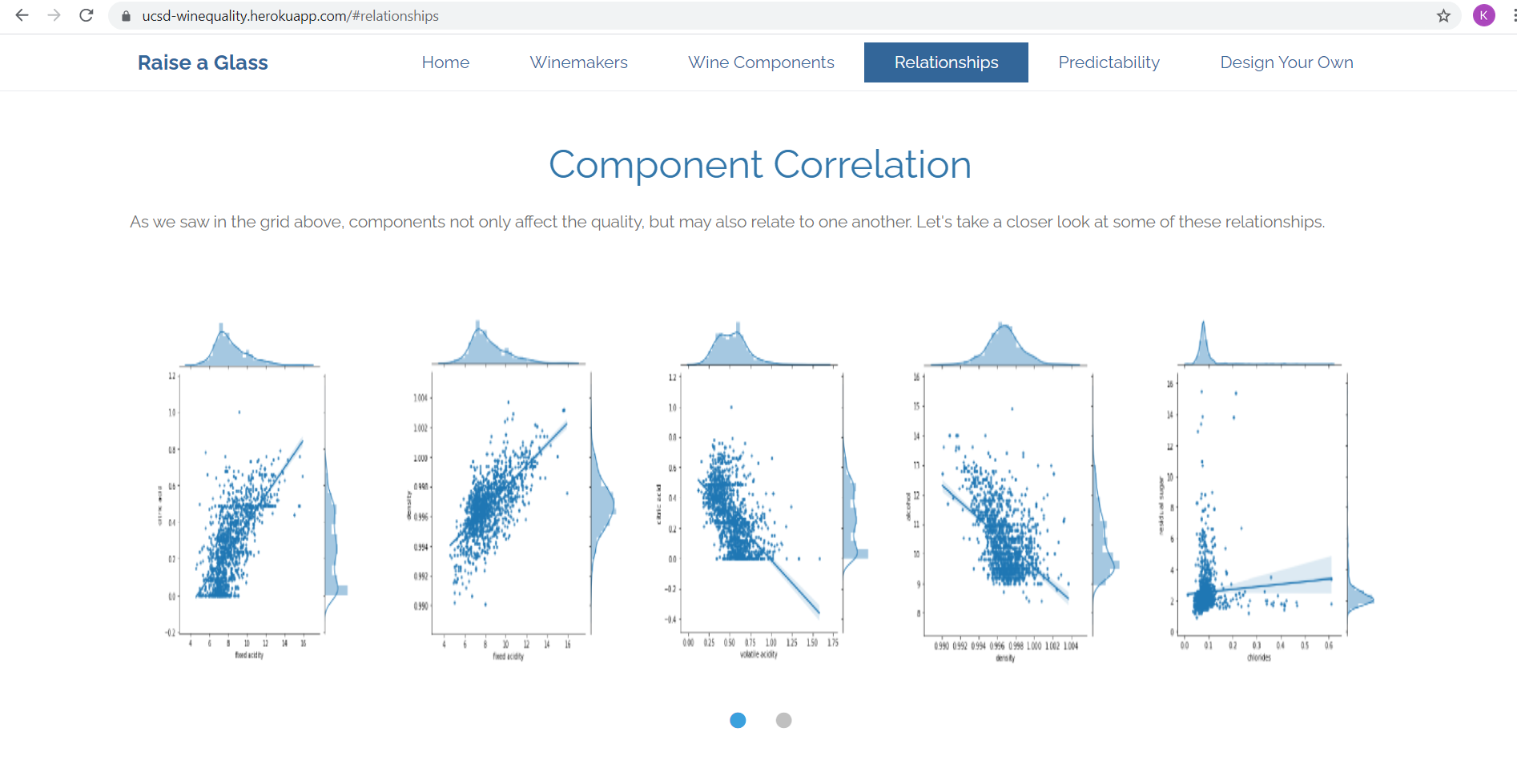

Our machine learning models were run with varying percentages of train and test data, ranging from a 75/25 split to 80/20. Our results ranged from 69% to 95%, the highest being from the Random Forest Regression, Random Forest, and XGBoost models. We were pretty happy with our 95% scores, which are pretty great if you ask us: that could make some pretty reliable wine-making! Once the model was established, we created several super-interesting graphs that you can find on the deployed app.

Deployment

The app has been deployed here: https://ucsd-winequality.herokuapp.com/. Check it out! Look at the awesome graphs that Tanlin and Rick produced. Play around with the beautiful gauge that Kate made! Have a taste … dream about what’s possible …

Final Thoughts

Even though we initially had trouble figuring out what we had to do with the data and the model, this turned out to be a really fun project and everybody got to contribute something. Great group of people. Cheers!

Sources

Wine attribute data: https://www.freecodecamp.org/news/using-data-science-to-understand-what-makes-wine-taste-good-669b496c67ee/

Modeling: Understanding Random Forest How the Algorithm Works and Why it Is So Effective Tony Yiu Jun 12, 2019 https://towardsdatascience.com/understanding-random-forest-58381e0602d2

Wine Quality Prediction Analysis | Machine Learning | Python Hackers Realm Oct 21, 2020 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W25TEa93T_I

Predicting Wine Quality with Several Classification Techniques A data science project walkthrough with code! Terence Shin May 7, 2020 https://towardsdatascience.com/predicting-wine-quality-with-several-classification-techniques-179038ea6434

How to use machine learning to judge the quality of wine Intro machine learning project Kylie Ying, May 19, 2020 https://youtu.be/BqDae4GPnu0

RAISE A GLASS!!!!